Don’t bother answering questions by the next pollster who calls to do a survey. You’re probably going to lie to him. Because “everybody lies.” And there’s no point in taking a survey if you’re going to lie. Besides, Google’s already got you on the truth meter.

That’s one of the main discussion points in the new book, “Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are.”

The blurb on the book says, “By the end of an average day in the early 21st century, human beings searching the Internet will amass 8 trillion gigabytes (GB) of data.” Every day, 8 trillion GB. What does that even amount to? Who knows, but it’s a lot. The average computer has about 4 GB of memory. A flash memory card in a camera may store 16 GB. We’re talking 8 trillion GB – daily.

So what are people searching? Pretty much everything, according to “Everybody Lies” author Seth Stephens-Davidowitz. And the data these searches reveal can be one useful tool for putting the human psyche under the microscope.

“People are honest on Google. They tell Google what they might not tell to anybody else. They’ll confess things to Google that they wouldn’t tell friends, family members, surveyors, or even themselves,” Stephens-Davidowitz said Tuesday in remarks about his book.

Take, for instance, some of the common confessional-style searches that Google gets: “I hate my boss,” “I’m happy,” “I’m sad,” or even “I’m drunk.”

Some of the searches can become rather morose and depressing. For instance, after the San Bernardino attack in 2015, in which 14 people were killed and another 22 seriously injured, top Google searches that soon followed included “Muslim terrorists” and “kill Muslims.” Stephens-Davidowitz says certainly it lacks context to try to guess what people were trying to express in the search, but it also provides guidance.

Here’s one way the data were used. Shortly after the attack, President Obama delivered a speech to try and calm fears about Muslims in America. But his grandiose sermonizing about opening America’s hearts backfired. Even during the speech, people got angrier. But at one point, Obama said that we have to remember that Muslim-Americans are our friends and neighbors, they are sports heroes, and members of the military who are willing to die to defend this country.

Immediately, while the speech was still being given, Google searches for “Muslim athletes” spiked. The increase was so notable that when Obama gave a speech a couple weeks later on the same topic, he skipped the lecturing and focused on the contributions of Muslim-Americans.

Stephens-Davidowitz argues that while Obama’s sermon didn’t tell anybody anything that they didn’t know, the line about sports heroes provoked curiosity, provided potentially new information, and redirected attention. This may not indicate that there’s a science to calming fears after a terror attack, but it does show the power of the data to change how people act and react.

Stephens-Davidowitz says part of the reason why data searches are more useful than old-fashioned survey questions is because people tend to lie in surveys to make them look good. It’s called social desirability bias. It happened during the elections of 2008.

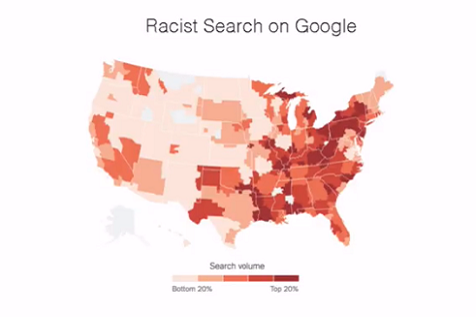

During that time, most Americans surveyed said Obama’s being black didn’t matter. Yet during the election, there was a spike in racist term searches. And graphing that data revealed that racist term searches were geographically divided between East and West. While correlation is not causation, where the racist term searches spiked, Obama lost about 4 percentage points of the vote over the previous Democratic candidate (John Kerry) in Democratic strongholds. He also generated a 1-2 percentage point increase in the number of African-Americans who voted.

The book, “Everybody Lies,” isn’t entirely about politics. It talks about a variety of topics like the stock market, crime, sports, and of course, sex, a hugely commercial enterprise on the Internet. In one example about the truth of big data, Stephens-Davidowitz notes that American women said in recent polling that they had sex (hetero and homosexual sex) once a week and used condoms about 20 percent of the time. Extrapolating the numbers, that would mean about 1.6 billion condoms were used that year. But asking men the same question (about hetero and homosexual sex) resulted in just 1.1 billion condoms allegedly used that year.

So who’s telling the truth, men or women? Neither. According to sales reports, just 600 million condoms were sold during the year in question.

Stephens-Davidowitz conjectures that people have an incentive to tell the truth to Google in a search, more so than to a pollster asking a survey, because they need information. For instance, an increase in the search volume for voting places in an area in the weeks leading up to an election is more likely to reveal whether turnout is going to be high in that location than whether a pollster finds that 80 percent of the people say they will vote.

But is Internet search a digital truth serum? Is it the best way to get real answers? Yes and no.

It depends on how available other high quality data are. For instance, Google flu, which attempted to determine how sick the population was during flu season based on searches about symptoms, was not as accurate as flu modeling currently used by government agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Furthermore, what people search doesn’t explain why people search. Likewise, Google doesn’t identify who’s searching so we don’t know if the search is a representative sample of the population. There’s no way of knowing what an absolute level of response would generate. For that, we need lots of different types of data.

But Internet searches may be useful in measuring the human psyche more so than in predicting futures. Big data can be helpful in looking at information that does not require very precise numbers. Predicting an election within 5 percentage points isn’t helpful. But it probably is not a big deal to be off by 10 percent when counting the number of condoms used in a year.

As for topics like child abuse, Stephens-Davidowitz says that he’s not actually sure how to use the data to help governments and protective agencies develop programs to identify and address abuse, but that it’s certainly information that would be helpful in filling a gap in reporting. And like any pollster worth his salt will tell you, being able to ask the right question is one vital way of getting to an accurate answer.