Last spring, Washington was locked in partisan combat over unemployment insurance. You may remember this showdown as that time when Congress came to a screeching halt over intractable differences and both parties said the sky would fall if the other guys got their way. Since this sort of episode is such a rare occurrence for the hyper-productive compromise fiends who serve in our legislature, I’m sure you remember it clearly.

What was the germ of the dispute?

What we fight about when we fight about unemployment insurance

On one side, many commentators from the left to the center-right saw extending the emergency benefits as a no-brainer. The labor market was still enfeebled, they argued, so keeping the checks flowing was the only compassionate thing to do. Besides, they contended, the fact that few job openings were available would limit the economic inefficiency that comes with subsidizing joblessness. It makes a lot more sense to help an out-of-work person pay the bills if she has zero job openings at her fingertips than if she had dozens to choose from, and these voices insisted that our turbulent economic times look more like the former situation than the latter. And the cost of benefits was a small price to pay to keep unemployed Americans actively looking for work — one of the requirements for receiving the payments.

Some conservative skeptics weren’t buying it. They saw the emergency extension as a short-term stopgap whose time to expire had come. They argued that the insurance payments effectively reward joblessness, and that propping up unemployed people with taxpayer dollars reduces the urgency with which they’ll seek work, thus perpetuating the very economic sluggishness they are meant to ameliorate.

So far, this looks like a standard policy fight with a massive impact on people’s lives. Here in D.C., the debate was hyped as something close to a life-or-death matter for millions of Americans. But a little bit of extra research can add some valuable context.

The conventional debate neglects a key question

Cristobal Young, a Stanford sociologist, has studied the non-pecuniary effects — that is, effects that aren’t purely financial — that unemployment insurance has on the lives of recipients. Specifically, Young tracked the self-reported happiness (“subjective well-being”) of different groups of people caught up in different economic circumstances. What he found is seriously surprising.

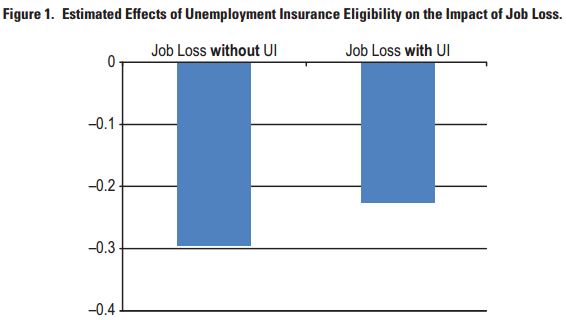

In this graph, Young has calculated the happiness of impacts of losing your job and receiving no unemployment insurance (on the left) and losing your job but receiving the benefit (on the right):

The similarity is remarkable. To hear progressive commentators tell it, job loss in the absence of unemployment insurance is like stepping straight into Hell, and the benefits do a tremendous amount to lift up hard-luck Americans. But here, we see a different story: Unemployment benefits merely take a little bit of the edge off the happiness downdraft from being laid off. To be sure, the financial help cuts back on some stress at the margins. But just as clearly, involuntary idleness brings a massive psychological cost that mere money can hardly touch.

Young agrees with that analysis:

Job loss into unemployment…brings on deep distress that is greater in magnitude than the effect of changes in family structure, home-ownership or parental status. The distress of job loss is also hard to ameliorate: family income does not help, unemployment insurance appears to do little and even reemployment does not provide a full recovery.

One more fascinating brick for the tower of evidence that feeling productive and earning one’s own way are critical components of human happiness. Losing our shot at earned success deals a blow to our souls.

These results should challenge both the left and the right

Young’s findings have implications that should challenge liberals and conservatives alike. On one hand, his results suggest that laid-off Americans who are cashing unemployment checks are still miserable and would vastly prefer to be working. This cuts against the Republican narrative that these people are willful loafers who have it too easy.

But Young’s work should also trouble progressives who prioritize welfare programs above broader pro-growth policy. It could not be clearer that improving Americans’ lives ultimately comes down to fostering a functioning, growing economy, not tinkering with the levers of social policy. The old saw that “the best social program is a job” isn’t just a right-wing cliche. It’s a truth about human well-being — and one that our leaders would do well to remember.