You thought this was resolved in the ’90s, didn’t you? It wasn’t.

“Almost one-third of Americans aged 18 to 60 report that they personally know someone who has not married for fear of losing means-tested benefits.”

That’s right, the marriage penalty still exists on families who receive government subsidies, and it is impacting more families as the safety net expands.

Now, the bias up the social ladder has traditionally been to assume that people who have kids without getting married are of questionable moral character because who would go have a baby without having a stable household, right? After all, studies show that children raised by their biological parents in married households have a likelier chance of success in school, a stable job, and upward mobility.

That notion of planning your marriage, then your family is outdated in a lot of communities, not least because when is it ever a good time to have a kid? So maybe the decision to not marry is not a question of moral repute, but in fact a question of public policy working against a loving family whose only commitment phobia is filling out the paperwork.

At least 43 percent of families with children 18 and under receive some kind of means-tested aid from the federal government, from Medicaid to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program funds. That number goes up to 47 percent for families with children five and under. And this is what they are likely to face if they marry.

… 82 percent of those in the second and third quintiles of family income ($24,000 to $79,000) face this kind of marriage penalty when it comes to Medicaid, cash welfare, or food stamps. By contrast, only 66 percent of their counterparts in the bottom quintile (less than $24,000) face such a penalty. …

Couples where each partner’s individual income is near the cut-off for means-tested benefits—are about two to four percentage points less likely to be married if they face a marriage penalty in Medicaid eligibility or food stamps. Most of these couples are in the second and third quintiles of family income for families with children two and under ($24,000 to $79,000).

Indeed, this recent report on the marriage penalty notes that couples’ combined income in that second and third quintile of earners ($24,000 to $79,000) could face penalties of lost benefits up to one-third of their income if they were to marry.

A valid question is why has the social safety net grown so large that families making nearly $80,000 are still receiving benefits? That may make sense if you’re talking about a family in Brooklyn or around the Beltway outside Washington, D.C., or Honolulu, or San Francisco, for example, but that’s certainly not the situation in Indianapolis, Louisville, Omaha, Memphis, Tulsa, and so on.

The answer lies in the decision not to marry. If one unmarried person is reporting income to an agency, then the household earnings don’t get counted as $80,000, it only gets counted as the one family member’s income. A combined income would phase out benefits whereas a reported single income would qualify.

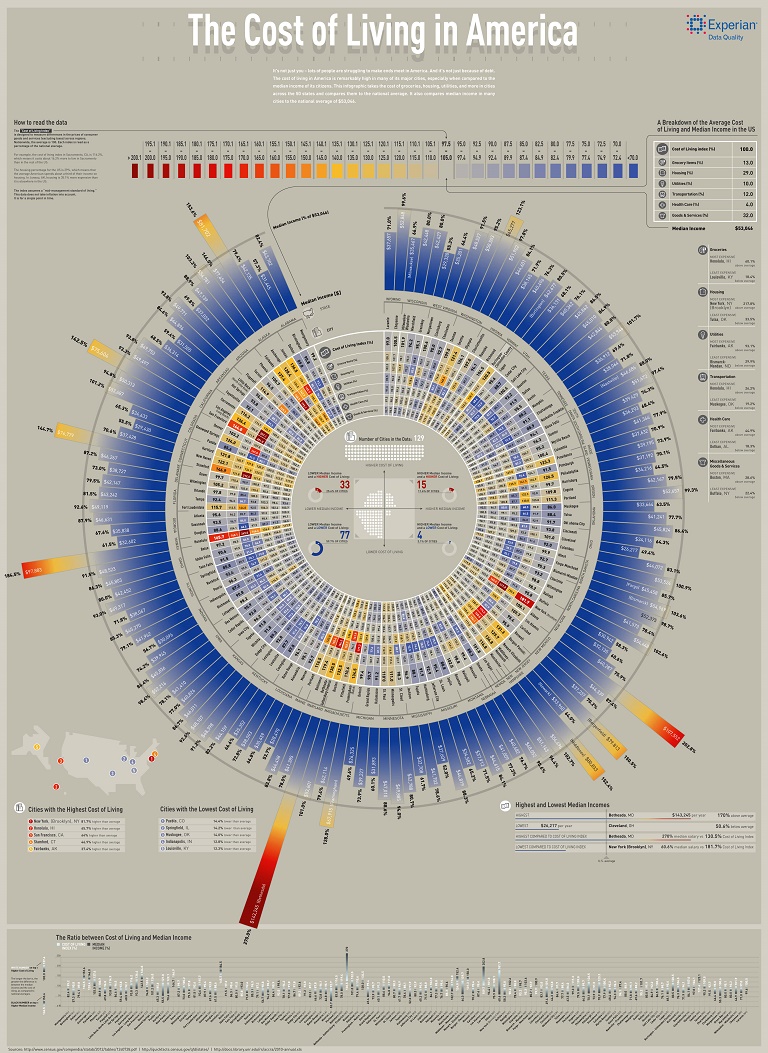

Certainly, no one wants to see anyone in need unable to receive the staples of shelter and food, but as the below infographic demonstrates, 59.7 percent of cities surveyed by Experian (click on it to enlarge) have a lower median income and a lower cost of living than the national average so many recipients can in fact afford to live without federal benefits.

The report does not challenge the expansion of the safety net to the lower-middle class, but it does raise the question of whether public policy discourages couples from marrying. And as the evidence shows, a significant minority of Americans say they have seen marriage ruled out because of the policies.

So how does government policy correct itself to not penalize lower-middle-class couples for being married when they start their family? The report makes four suggestions:

– In determining eligibility for Medicaid and food stamps, increase the income threshold for married couples with children under five to twice what it is for a single parent with children under five. Such a move would ensure that couples just starting a family do not feel pressured to forgo marriage just to access medical care and food for their families. The cost of this policy change would be limited, since it would only affect families with young children.

– Offer an annual, refundable tax credit to married couples with children under five that would compensate them for any loss in means-tested benefits associated with marrying, up to $1,000. This would send a clear signal that the government does not wish to devalue marriage and, for couples, it would help to offset any penalties associated with tying the knot.

– Work with states to run local experiments designed to eliminate the marriage penalty associated with means-tested policies. States could receive waivers to test a range of strategies to eliminate penalties in certain communities, and to communicate to the public that the penalties are no longer in force there. Successful experiments could then be scaled up to the national level in future efforts to reform means-tested policies.

– Encourage states and caseworkers working with lower-income families to treat two-parent families in much the same way as they do single-parent families. For instance, states could ease the distinctive work requirements that many have in place for two-parent families receiving cash welfare. Reforms such as this one would put two-parent and single-parent families on a more equal footing when it comes to public assistance. More generally, policymakers and caseworkers should try to eliminate policies and practices that effectively discriminate in favor of single-parent families.

Read the report on the marriage penalty’s impact on lower-middle income families.