The United States is at an awkward crossroads. At a time when the 2016 presidential election is creating a bitter divide, arguments between neighbors and friends are seemingly at odds with the reality of the U.S. economy. The question is not whether the economy can produce jobs, the question is why did America stop working?

Social services and nonprofit leaders have expressed frustration. Jobs are available. Employers are creating openings. But it is becoming harder and harder to find workers to fill them. To this point, too few Americans are stepping up to take these positions.

As a recent Wall Street Journal article reported:

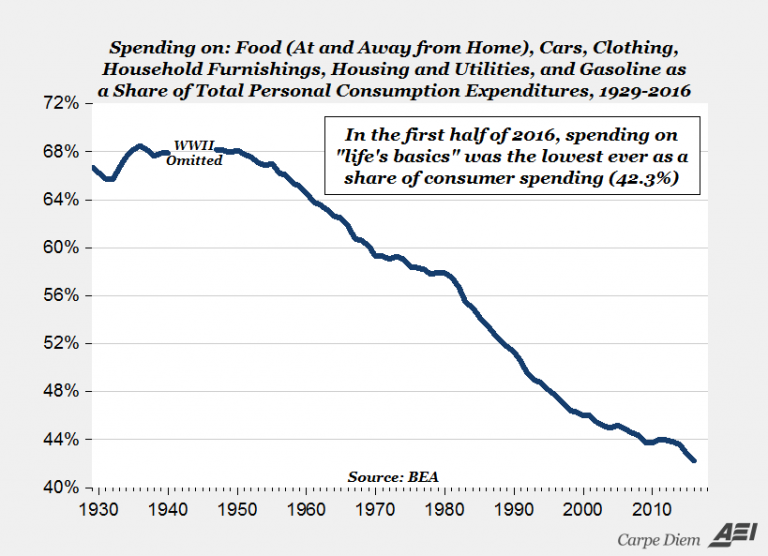

Retailers are scrambling to hire holiday-season workers despite an unusually early start on recruiting this year, creating a collision among employers for temporary help in a tight labor market.

Data from job-search site Indeed.com shows retailers, and the warehouse and logistics firms they compete with for seasonal labor, started searching for temporary workers in August, a month earlier than in recent years. This suggests retailers and other firms “anticipate stronger consumer demand and expect that it will be harder to find the people they want to hire,” said Indeed economist Jed Kolko.

Last year, more than one in four retail workers hired in the fourth quarter of 2015 started their jobs in October, the highest share on records back to the 1930s.

Companies and analysts say a number of trends are converging. The holiday-shopping season is starting before Halloween for many consumers, rather than the traditional day after Thanksgiving. There are fewer workers available, due to unemployment holding around 5% for the past year. And retailers are facing tougher holiday-hiring competition from logistics firms and distribution centers, which have grown along with e-commerce. …

The pace of overall hiring has slowed a bit this year compared with 2015, but has remained strong enough to absorb new entrants into the labor force, and keep the unemployment rate in check. As a result, wages have started to inch up. That is particularly true for the lowest-paid workers. Weekly wages for workers at the 25th percentile—someone who makes roughly $14 an hour for a full-time job—have increased 4% in the third quarter from a year earlier, compared with a narrower 3% increase for the median worker, according to the Labor Department.

Keeping the economy on track and producing opportunities will be a major task for the next administration, but so will addressing the reasons why so many potential workers are staying on the sidelines. Should we be most concerned about work disincentives in safety net programs, health challenges, or the lack of affordable child care? We have to find the answers to help more Americans go to work.

But these are only a few of the challenges the labor market faces today. In a new volume edited by AEI Director of Economic Policy Studies Michael Strain, 21 of the country’s most prominent economists answer some of our most pressing questions: Is productivity the most important determinant of compensation? How can we build workers’ skills? What should we do about workers who are especially difficult to employ?

Strain gets to the core of these policy issues by speaking to the overall reason why they matter. The chief driver is not the need for a smooth economic engine, but the personal worth that working creates. As Strain eloquently explains:

If I asked you to tell me about yourself, there’s a good chance you’d begin with your job. ‘I’m a teacher.’ ‘I’m a nurse.’ There is something noble behind the impulse to lead with your occupation: we want to contribute to society,and for many of us employment is a key avenue for social contribution. Especially in a market economy— where comparative advantage is rewarded and incentives exist to discover yours, nurture it, and apply it—who we are is, to a large degree, how we choose to contribute.

Work allows us to provide and care for our children. (That the national income statistics don’t reflect much of this work says nothing about its immense value.) Work fosters community—there is something unique and edifying in enjoying the company of your coworkers after that long, hard project is finally completed or the work week has come to a close. The best antidote for boredom and vice is often a good job. Among other features, the expressiveness inherent in work—its creative element—is, or at least can be, deeply spiritual.

Indeed, work is central to the flourishing life. And public policy, in its effort to promote the common good, is properly interested in helping to create a vibrant labor market in which individuals can earn their own success, realize their potential, and enjoy the dignity that hard work provides.

Importantly, all nine of the topics covered in the volume — which range from immigration and corporate taxes to income inequality and worker mobility — are addressed twice from different perspectives — reflecting that the competition of ideas is the best way to solve the nation’s toughest problems.

As this unpleasant election season comes to a close, these important challenges will need to be addressed by the next administration and Congress. Hopefully, come January, both parties will find common ground on a handful of important policy reforms that will be good for the country.

— Robert Doar contributed to this discussion.