The New York Times recently published an essay entitled “Why You Hate Work.” Its authors work for a firm that advises employers on making workers happier, and they see the average workplace as a dreary place in desperate need of their services:

Even if you’re lucky enough to have a job, you’re probably not very excited to get to the office in the morning, you don’t feel much appreciated while you’re there, you find it difficult to get your most important work accomplished, amid all the distractions, and you don’t believe that what you’re doing makes much of a difference anyway. By the time you get home, you’re pretty much running on empty, and yet still answering emails until you fall asleep.

Yikes. Described that way, modern work sounds like the myth of Sisyphus, a Greek ruler who displeased the gods. His punishment was to push a massive boulder up a mountain, watch it roll back down, and do it all over again every day for eternity. Is the 9-to-5 life just a new version of this torment?

Some surveys back up the narrative

The short answer is that it depends on how you ask. Several surveys would seem to substantiate the authors’ claims. For example, their column cites a poll that their company conducted with the Harvard Business Review. It asked thousands of white-collar workers whether their work lives contain things like:

- “Regular time for creative or strategic thinking”

- “Opportunities to do what is most enjoyed”

- “Connection to your company’s mission”

- “Overall positive energy”

For most of the good things the survey asked about, pluralities of employees said their jobs lack these things. This survey looks a lot like Gallup’s annual “State of the American Workplace” survey, which also asks about a number of specific criteria:

- “At work, I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day.”

- “I have a best friend at work.”

- “The mission or purpose of my company makes me feel my job is important.”

These polls paint a disheartening picture. In 2013, only 30% of American workers checked off enough of Gallup’s boxes for the survey to categorize them as “engaged and inspired.” This was enough to persuade the media that we are a nation in crisis. “Americans Hate Their Jobs, Even With Office Perks,” declared one headline. “Most workers hate their jobs or have ‘checked out,'” insisted another.

Things look bad. But how useful are these kinds of surveys? That’s an open question.

The problem with top-down surveys

Polls like the Gallup survey rely on top-down methodology: Experts invent a list of statements that they imagine flourishing employees would agree with. Then they ask workers if those statements describe their experience. This neglects the fact that different people expect different things from their work.

Imagine a man who adores playing chess. He eats and breathes chess, but isn’t quite talented enough to earn a living as a professional. As a result, he grabs the highest-paying job he can find, harboring no illusion that the work will be deeply satisfying. He simply wants to pay the bills and get home to the game he loves. This guy’s work experience would flunk the Gallup test, yet his job fills precisely the role in his life that he wants.

To be sure, this is not most of us. The bulk of ordinary men and women have professional aspirations and out-of-work priorities alike. But the fact remains that no two people have identical lives or identical expectations for their careers.

So rather than telling people whether they are happy or unhappy at work based on a long list of ambitious criteria, perhaps we should just ask them the question directly. “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your job?”

Instead of asserting what a great job looks like, this wording invites the respondent to apply his or her own standard. This is precisely the question that the University of Chicago’s General Social Survey (GSS) has asked Americans for decades. Their data tell a very different story.

Ask a different question, get a different answer

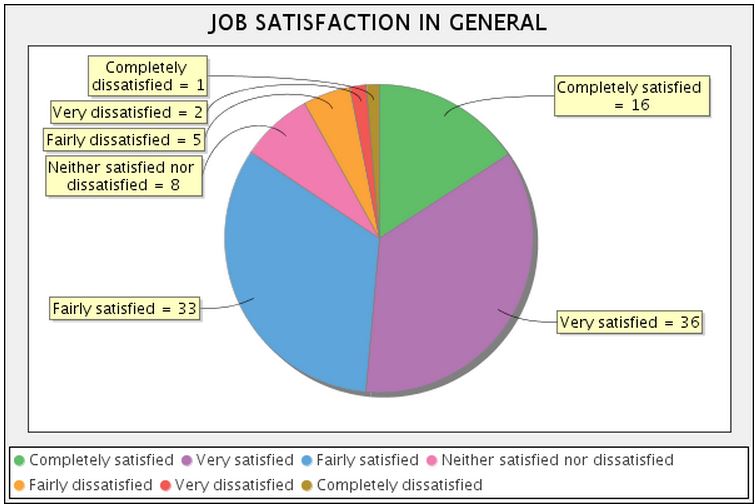

As the chart below indicates, the 2012 GSS found that 36% of the country is “very satisfied” with their jobs. Add in the 16% who are even happier (“completely satisfied”) and the 33% who are “fairly” satisfied, and we have a staggering 85% majority of Americans who generally like what they do.

I know what you’re thinking: “Successful people must be skewing the data.” Conventional wisdom suggests that high-earning professionals who love their work are pulling the average up, and that Americans who work in less glamorous roles must be mostly unhappy. Right?

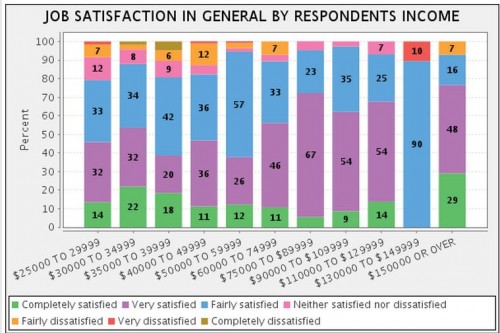

Wrong. Look what happens when we analyze the data by income:

As income increases, there does seem to be a slight upward trend in the proportion who are “satisfied” – that’s the blue bars and everything below. But even at low income levels, job satisfaction is vastly higher than many might expect. Among Americans whose annual pay ranks in the low $30,000s, for example, fully 88% are generally satisfied with their jobs.

In short, this massive and well-respected survey finds that the vast majority of Americans at every income level are reasonably happy with their jobs.

Elites may feel overworked and under-appreciated. Highly-educated folks may feel sure that people in “dead-end jobs” must be miserable. But once we look past the apocalyptic headlines and dig into the data, there is good evidence that Americans derive real satisfaction from earning our success on the job.