Dr. Sally Satel is a psychiatrist who has spent more than 25 years treating patients with opioid addiction. She has seen highs and lows that would make a roller-coaster jealous. But she also sees light on the horizon when it comes to treatment.

With public attention and resources now closely trained on the opioid epidemic, there is a real opportunity for enlightened systems of care. Never before in the history of addiction management have there been so many different therapeutic elements to apply in combination to promote recovery. But we can’t afford to focus on just one set of these tools under the false idea that addiction is a disease like any other.

Why not just treat addiction like a “chronic illness”? As Satel explains, it is much more involved than just a medical diagnosis and prescription plan.

But first, we must acknowledge the problem, and it’s big. In the U.S. today, opioid use is skyrocketing. Some shocking statistics reveal its impact.

With an estimated 2.6 million people addicted to opioids—including heroin, fentanyl and oxycodone—the toll is daunting. Fatal opioid overdoses have risen from around 8,200 in 1999 to 33,000 in 2015, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, making them a leading cause of accidental death. Last year, deaths from heroin slightly edged out gun homicides for the first time since the government began keeping such data.

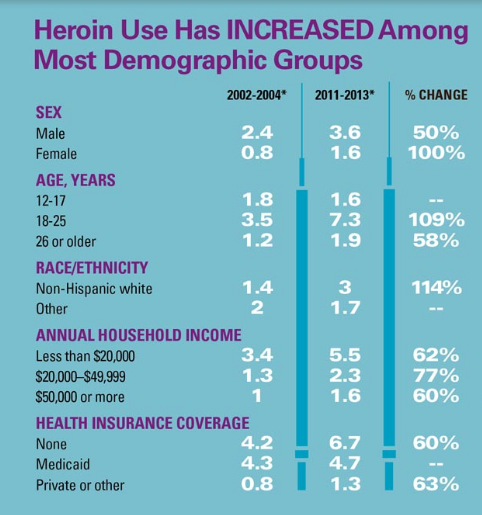

The CDC reports that deaths from heroin overdoses quadrupled between 2002 and 2013. Heroin use spans the gamut; its use is rising among men and women, all age groups, and all income levels.

So what needs to be considered when dealing with addiction?

- Medical treatment: Opioids are combated with anti-opioid medications. Many people have heard of methadone, but other options, like buprenorphine, or “bupe,” have been rising in popularity. With it come hazards: proper dosage and handling of anti-opioids is critical to preventing abuse. Monitoring patient dosage is a matter requiring close attention.

- Causes of Relapse: Satel notes that 40-60 percent of addicts drop out of treatment before they’re done. This is partly due to ambivalence on the part of the addict, partly because of the overwhelming pull of addiction, and partly because treatment plans are conducted by the wrong doctor in the wrong environment. In addition, often times, the treatment plan is too rapid or doesn’t address the triggers that cause people to return to drugs.

- Restoration: Addiction doesn’t just ravage the addict’s body, its impact is savage toward everyone around. Not just treating the cause, but looking at ways to cope with the future is imperative. Without it, the toll continues on an addicts’ and their families, their ability to work, their social networks, and their ability to find satisfaction through something other than drugs.

- Enforcement: In the desire to not overwhelm the public health or criminal justice systems, drug courts are looking for ways to influence addicts without destroying the possibilities of their being able to live a drug-free future. This means ruling with degrees of consequence like community service or “flash incarceration,” and providing other carrots and sticks, including expunging the record of someone who completes treatment.

Managing the situation of dealing with an addict is not easy, Satel notes.

I speak from long experience when I say that few heavy users can simply take a medication and embark on a path to recovery. It often requires a healthy dose of benign paternalism and, in some cases, involuntary care through civil commitment. Many families see such legal action as the only way to interrupt the self-destructive cycle in which their loved ones are caught. Users sometimes want it, too.

With an explosive rise in addiction, appropriate government policy can help. Satel says Donald Trump’s blueprint during the election was consistent with the Comprehensive Addition Recovery Act that passed Congress this summer, though is only partially funded. The bill calls for expanding addiction treatment access, funding for diversionary programs such as drug court, and funding for naloxone (the opioid antidote that instantly reverses the respiratory suppression of overdose), among other things. This is heading in the right direction, she says.

If you deal with addiction in your family, it’s important to get help. You can call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or check out the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration for resources.

Read Sally Satel’s article on treating opioid addiction.

Get more statistics on America’s opioid epidemic.